Spoiler: The narrative of the oblast being “dragged down” by national minorities during EIT does not hold water. This, however, does not cancel the question of the quality of education and teaching of the Ukrainian language at schools for national minorities.

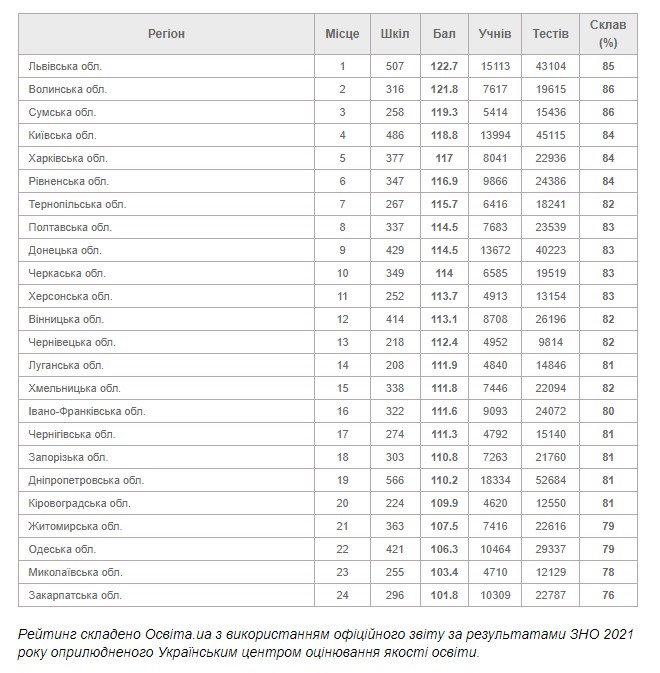

A few days before September, 1 the internet portal Osvita.ua published the annual External Independent Testing (EIT) rankings of all of the Ukrainian oblasts. Zakarpattia came last yet again.

By ‘yet again’ we mean at least 4th consecutive year since these rankings were first published.

Unfortunately, these truly shocking statistics are lost in the hustle and bustle of the last summer days and the festivities of the 1st day of school.

To ignore this problem will not only bear no fruit, but will also prove dangerous, since these abysmal results of the Zakarpattia oblast come along with a quite sensitive and complex problem of national minorities living in the region. In particular, an issue of language of instruction has proven quite contentious in view of the new law that has been adopted by the Ukrainian parliament. This law has also led to a Ukrainian-Hungarian altercation and the aggravation of the relations between Ukraine and its Western neighbors and partners, such as Romania, Poland and Bulgaria.

Infopost.Media has tried to puzzle out the EIT results. In particular, we wanted to find out if there was any interdependence between the EIT results and the language of instruction. This topic, unfortunately, has fuelled lots of speculations both in and out of Ukraine.

For reference: There are 604 schools in Zakarpattia, 117 of which are national minority schools. Hungarian is the language of instruction at 101 schools, 14 schools teach their schoolchildren in Romanian, with 1 Russian and 1 Slovak school.

How the ranking lists are drawn

The aforementioned ranking lists are compiled on the basis of the average marks that the participants of the EIT receive. They are then calculated as the arithmetic mean of all the tests, including the ones that the participant has failed.

The tests that have been failed receive the value of ‘0’, which means that the average mark may be lower than 100 points.

If a school leaver has not showed up on the test day, this test will not be considered during calculations.

The percent marker of those who have received the necessary number of test points is also important.

The library of the 3rd school named after Zsigmond Perényi in Vynohradiv. Photo credit: Dmytro Tuzhanskyi

Zakarpattia in the rankings

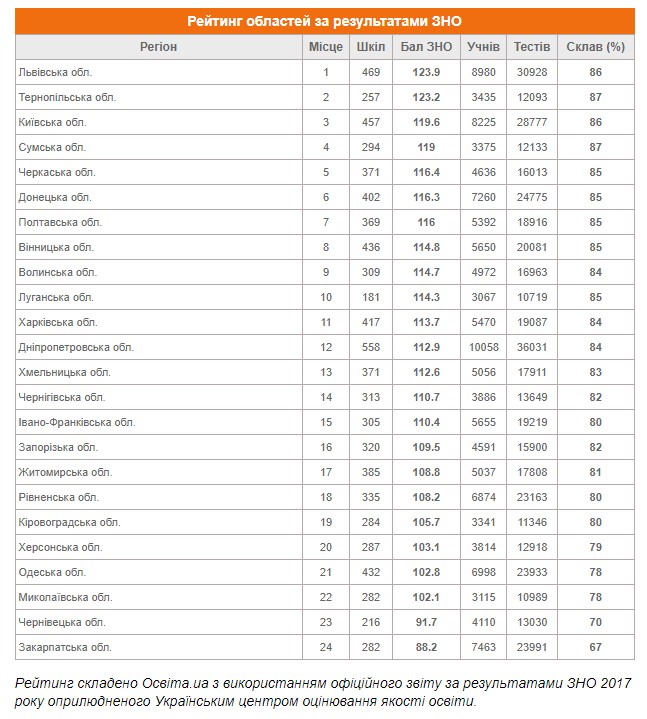

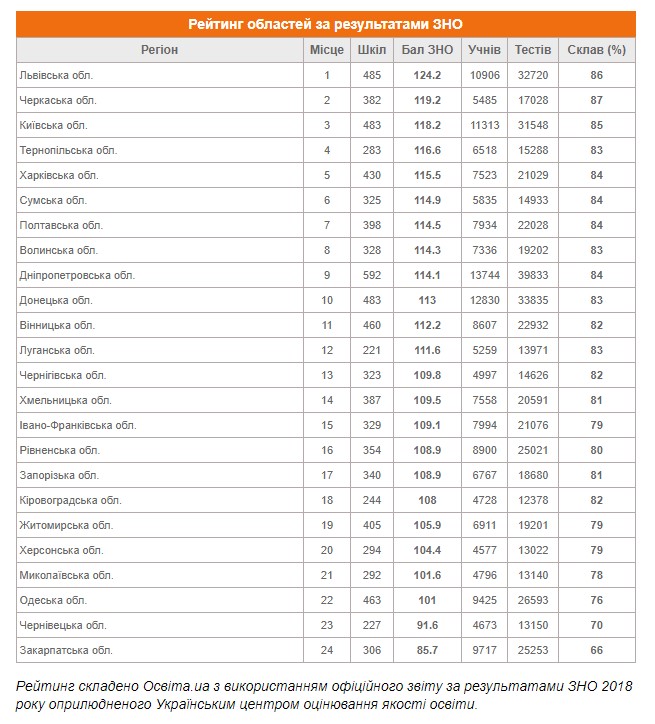

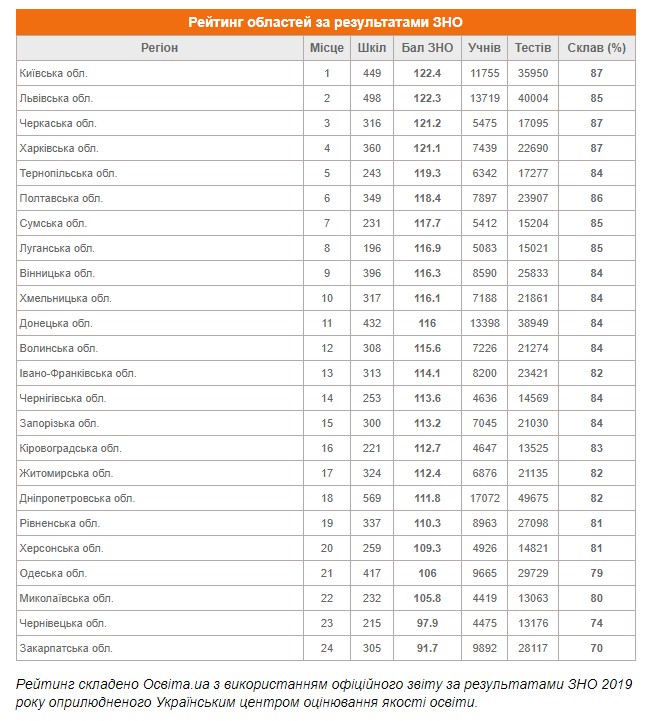

Starting from 2017, the Zakarpattia oblast has been ranking last for 4 consecutive years.

In 2017 the region came last with the average score of 88,2. Moreover, only 67% of the region’s schoolchildren took the EIT. The Lviv oblast topped the ranking list with the average score of 123,9 and 86% of the region’s schoolchildren who took the EIT.

In 2018 things turned from bad to worse in Zakarpattia. The average score and the percentage of school children taking the exam dropped, with 85,6 and 66% respectively.

2019 was a relatively successful year for Zakarpattia. The average score stood at 91,7 with 70% of schoolchildren having sat the exam. These results, however, did not help the region to get out of the bottom of the rankings.

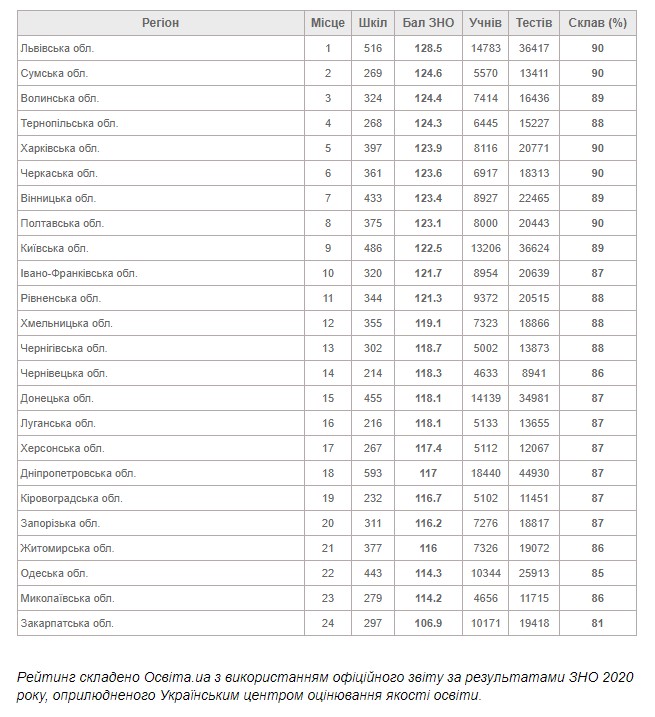

2020 showed even better results. Finally, the region surpassed the 100-mark, having reached the average score of 106,7, with 81% having taken the EIT.

Presumably, this has most likely to do with the fact that the Ukrainian Ministry of Education had lowered the admission score for the Ukrainian language tests for the schoolchildren representing national minorities.

In 2021 Zakarpattia also ranked last. The region’s performance has deteriorated compared to the previous years. The average score has dropped to 101,8 with only 76% of school children having achieved the admission score.

The all-Ukrainian tendencies in the rankings

We would also like to point out that during all these 4 years the Zakarpattia oblast has been accompanied by the Odesa oblast (4th place at the bottom in 2017 and 2019, 3rd place at the bottom in 2018, 2020 and 2021) and the Mykolaiv oblast (3rd place at the bottom in 2017 and 2019, and the penultimate place in 2018, 2020 and 2021).

Before 2020 the Chernivtsi oblast had also been keeping the above-mentioned oblasts company. In 2017, 2018 and 2019 this oblast took the penultimate place.

However, in 2020 and 2021 the Chernivtsi oblast suddenly left the company of outsiders, having become a decent average performer with the 14th and 13th place in the rankings of the respective years.

- Interestingly, this occurrence coincided with the fact that in 2020 the admission score for the Ukrainian language tests was lowered for the schoolchildren representing national minorities.

We are about to check if such improvement was coincidental. If not, we are planning to find out the reasons for 2020 becoming a game-changing year for the success of the Chernivtsi oblast.

A Slovak school in Uzhhorod. Photo credit: Фото Varosh

Important details of the EIT results that impact the rankings

What are the reasons for Zakarpattia’s weak performance?

Having spoken to people involved in the educational process (conditional sampling of several schools’ directors), we have singled out 4 main factors affecting the quality of education in the Zakarpattia region.

- A high migration (and emigration) level in the region, in particular, among teachers;

- A low level of parents’ involvement into their kids’ education due to the high migration level and large-scale work migration abroad;

- Over 60% of rural population, which makes it difficult to maintain a high education level in view of lack of resources, especially human resources;

- The polyethnicity of the region and a low level of Ukrainian language teaching at the national minorities schools, especially due to: 1) unsatisfactory methods of teaching of Ukrainian as a foreign language; 2) maladjustment of the language component in curricula; and 3) lack of bilingual teachers.

Unfortunately, the issue of polyethnicity is most often brought up in public discussions as the decisive one. Also, it is explained in simplified form, purporting that Hungarians and especially Romanians (since there are more schools of the latter minority) are weak in speaking and learning Ukrainian.

A piece on the Slovak school in Uzhhorod

However, this is not only a simplified form. The whole narrative is quite manipulative, which can be substantiated by the local results of the abovementioned EIT.

For instance, we have compiled separate ranking lists for towns of Zakarpattia and its rayons as of 2021.

These are the rankings based on the number and percentage of those who have failed the EIT.

Thus, the Hungarians of the town of Berehove have shown decent results, even better than those produced by the residents of other towns of the region with no Hungarian minority.

The ranking of Zakarpattia’s towns looks like this: the first column shows the number of those who have not achieved the admission score, with the second column standing for the percentage of the general number of schoolchildren who have sat the EIT:

| № | Town | Those who have not achieved the admission score | % of the general number of schoolchildren |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Svalyava | 5 | 5,7% |

| 2 | Uzhhorod | 93 | 7,4% |

| 3 | Khust | 17 | 7,8% |

| 4 | Chop | 2 | 8% |

| 5 | Mukachevo | 103 | 9,6% |

| 6 | Berehove | 40 | 11% |

| 7 | Tyachiv | 10 | 11,4% |

| 8 | Rakhiv | 10 | 12,3% |

| 9 | Perechyn | 7 | 13,2% |

| 10 | Irshava | 10 | 13,7% |

| 11 | Vynohradiv | 36 | 16,5% |

Regarding the region’s rayons*, at first glance one may notice the possible correlation between the rankings and the ethnic composition of each of the rayons. However, poor performance of such old rayons as Rakhiv and Irshava (with the latter being monoethnic) calls this assumption into question.

| № | Rayon | Those who have not achieved the admission score | % of the general number of the schoolchildren |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Svalyava | 9 | 6,2% |

| 2 | Volovets | 6 | 6,7% |

| 3 | Mizhhir’ya | 21 | 7,9% |

| 4 | Perechyn | 15 | 12,9% |

| 5 | Velykyi Bereznyi | 11 | 13,1% |

| 6 | Mukachevo | 40 | 14,2% |

| 7 | Tyachiv | 94 | 14,8% |

| 8 | Vynohradiv | 79 | 16% |

| 9 | Rakhiv | 59 | 16,5% |

| 10 | Irshava | 71 | 18% |

| 11 | Khust | 90 | 21,1% |

| 12 | Uzhhorod | 46 | 25,4% |

| 13 | Berehove | 37 | 36,3% |

*it should be noted that this table deals with the administrative structure of the Zakarpattia oblast consisting of 13 rayons. This structure is still being used by the Ukrainian centre for educational quality assessment. As of now, there are 6 rayons in the Zakarpattia oblast.

Do ethnicity and language of instruction not play a decisive role?

However, if we take a look at the situation in villages, we will see that in 2021 the villages dominated by the Hungarian minority have at first sight shown extremely poor results in such subjects as the Ukrainian language and literature (the tests in these subjects are obligatory.

-

- For example, in Szürte 33% of the participants have failed the test. In the village of Mala Dobron’ the number stood at 44%, whereas 50% have failed the test in the village of Esen’.

At the same time. In the Ukrainian-speaking village of Kam’yanytsya located in the same rayon, 46,6% of schoolchildren of the best performing school could not pass the Ukrainian language and literature test. In Serednye and Storozhnytsya 30% of schoolchildren have not passed this very test, either.

In other words, the performance of rural schools in Zakarpattia is just as poor as that of the Hungarian ones.

There are also other examples of urban schools with the Ukrainian language of instruction, whose schoolchildren perform much worse at the Ukrainian language test than those who attend the schools with the Hungarian language of instruction.

In Uzhhorod, 100% of the Hungarian lyceum have passed the Ukrainian language EIT.

The results of the school Nr 10 of Uzhhorod are a bit worse, with 14% of students having failed the test. At the same time, this result is not that poor, since, for instance, in the school Nr 9 with the Ukrainian language of instruction 18,52% of schoolchildren have failed the test. The result of the school Nr 19 with the same language of instruction is even worse, 20%, never mind the Centre for technical and vocational education – 40% of its pupils have not passed the test.

This year the Zakarpattia oblast lyceum with enhanced military and physical training named after the Heroes of the Red Field has been notorious for its 26% pupils who have not passed the Ukrainian language EIT.

The same happened to the local Centre for technical and vocational education and the Mukachevo agricultural college.

We deliberately have conducted a more thorough analysis of the Rakhiv rayon which is considered the centre of Zakarpattian Ukrainians with no representatives of the Hungarian minority except for the village of Yasinya.

- The situation in the Ukrainian schools is often much worse than that in the Hungarian ones located in other rayons. 55% of the schoolchildren at the school Nr 3 in Rakhiv have not passed the Ukrainian language and literature EIT this year. 38% of the schoolchildren at the school in the village of Kobylets’ka Polyana have failed this very test, 37% at the school in the village of Bohdan, 31% of schoolchildren in the village of Kostylivka, 28% in the village of Lazeshchyna…

Summary

So, what seems to be the problem? Why does Zakarpattia trail so much in the EIT?

Sadly, we do not know it yet.

Instead of drawing conclusions here, we would first of all like to raise the alarm. The situation in Zakarpattia appears to be catastrophic. Not only do determined measures need to be taken, there is also a need of in-depth and professional analytics that would help find the solution to a complex problem.

Otherwise, it will not be possible to solve it.

The editorial office of Infopost.Media is planning to continue studying this topic. For this reason, we are inviting you to follow our new and old publications on education in the polyethnic environment.

- How an ethnic Hungarian became an expert in Ukrainian philology and introduced a bilingual system of instruction at a Hungarian school. An interview with Gabriela Gomoki.

Petro Hoys and Dmytro Tuzhanskyi,

exclusively for InfoPost.Media