On April 3, 2022, many Ukrainian citizens of Hungarian origin will vote in Hungarian parliamentary elections. Because dual citizenship is officially banned in Ukraine the exact number these voters are not disclosed by the Hungarian authorities, though up to 40,000 Ukrainian citizens have voted in Hungarian elections since 2014.

The possibility for Hungarians abroad to vote in elections is at the core of an enormous architecture of efforts to support and engage Hungarian communities in neighboring countries, created, politically monopolized and systematically used by the ruling Fidesz-KDNP alliance led by Viktor Orbán.

The ultimate value of voters from Ukraine very much depends on the final turnout. Although 40,000 votes can’t guarantee even a single seat in parliament, they could prove decisive in some constituencies near the Ukrainian border, or on elections as a whole in case of a neck and neck contest. Experience from previous elections gives cause for deep concerns about the engagement of these voters in electoral fraud with questionable registration and “voter tourism.” Ukrainian citizens with Hungarian passports will most likely vote in Hungarian elections given the ongoing war and their participation may challenge the legitimacy and integrity of these parliamentary elections.

Moreover, Ukrainian citizens will be engaged in Hungarian elections against the backdrop of the deepest political crisis in bilateral relations between Hungary and Ukraine, which are at their lowest level in modern history. This crisis formally started in 2017 with debates regarding the newly adopted Ukrainian educational law, but since then this has expanded to cover all sensitive issues of bilateral relations. In particular: dual citizenship, Hungarian state funds in Ukraine, language and other minority rights of Hungarians, Ukraine’s integration towards EU and NATO, Russian malign and disinformation campaigns, interference into elections and internal affairs, national security, corruption, etc.

Hungarian community in Ukraine. Background

Ethnic Hungarians have lived in territories that are now the Transcarpathian region of Ukraine (Zakarpattia oblast, in Hungarian Kárpátalja) since the migration of Hungarian tribes to the Carpathian Basin at the turn of the 9th and 10th centuries. In Hungarian historiography this is referred to as “honfoglalás” – “conquest of the homeland” and considered by Hungarians as their historical lands, and themselves as indigenous people.

According to the last official Ukrainian census, conducted in 2001, a total of 156.6 thousand ethnic Hungarians live in Ukraine, which is 0.3% of the country’s population. At the same time, 151.5 thousand Hungarians live in the Transcarpathian region, which is 12.1% of the region’s population.

In 2017, with the financial support of the Hungarian government, a SUMMA 2017 survey was conducted to determine the actual number of Hungarians living in Ukraine, particularly in Transcarpathia. According to results 125,000 Hungarians and 6,000 Roma who identify as Hungarians live in Transcarpathia, and thus a total of 131,000, according to the research.

While not the majority, Hungarians still constitute a significant population in the main municipalities of the Transcarpathian region, including, Uzhhorod, Mukachevo, Vynohradiv, Khust. Berehove (Beregszász) in particular as it is the unofficial centre of Hungarian community with ethnic Hungarians mayors for the last decades, host to the editorial offices of several Hungarian-language outlets, and the Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education – the only Hungarian-language higher education institution in Ukraine, which is a kind of hub of various Hungarian institutions, including funds, endowments, etc.

Hungarian minority of Ukraine in political agenda of Budapest

The Hungarian community in Transcarpathia is not considered by the Hungarian government as diaspora, but as “Hungarians abroad” (külhoni magyarok), along with other Hungarian communities in neighboring countries living in the territories of so-called Greater Hungary, the pre-Trianon Peace Treaty Kingdom of Hungary. Hungary lost about a third of ethnic Hungarians and two-thirds of its territories in the post-First World War settlement.

“Trianon Trauma” is one of the key drivers of Hungarian government policy towards ethnic Hungarians living abroad, particularly under the Fidesz-KDNP. Supporting Hungarians abroad is not only a constitutional duty, but also a separate national policy of the government “Nemzetpolitikai”. Its essence is to preserve identity and communities in historical Hungarian lands, as well as unite the Hungarian nation across borders. The basis of the policy is not only to support Hungarian communities abroad through loans, grants or cultural projects, but to create autonomies of various kinds, from cultural and educational to political and territorial.

In practice, this includes creating and maintaining of closed Hungarian-language education systems from kindergartens to university, a network of cultural organizations that are simultaneously ethnic political parties for elections and funds to receive Hungarian government support.

Dual citizenship, along with political demands to legalize it, is a significant part of the Fidesz-KDNP government’s national policy. Since 1 January 2011, Hungarians abroad could obtain Hungarian citizenship through the simplified naturalization procedure. Ukrainian legislation does not officially recognize dual citizenship, but there is a gap in the legislation that (unlike Slovakia) prevents Ukrainian citizens from being punished for having a second passport. According to the latest public data released by the Hungarian authorities, as of February 2015, almost 94,000 Ukrainian citizens received Hungarian citizenship under a simplified naturalization procedure. At the same time, as of August 2015, a total of 124,000 applications for Hungarian citizenship were received from Ukraine.

In Transcarpathia, there is an extensive network of public and private (mostly at the churches) kindergartens and schools with Hungarian language education, as well as the high educational unit in Berehove, already mentioned.

The two main cultural and political organizations of the Hungarian community of Transcarpathia are:

- the KMKSZ (Kárpátaljai Magyar Kulturális Szövetség, The Transcarpathian Hungarian Cultural Association or The Cultural Alliance of Hungarians in Sub-Carpathia as translated by the KMKSZ itself, the leader is László Brenzovics.

- the UMDSZ (Ukrajnai Magyar Demokrata Szövetség, Hungarian Democratic Union of Ukraine). The leader is László Zubánics.

These organizations continue to compete with each other rather than cooperate. KMKSZ is a political ally of the ruling Fidesz party. UMDSZ is a political ally of the opposition Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), which lost its popularity, influence along with its status of Hungary’s main opposition party, 12 years ago. Consequently, KMKSZ is not only stronger due to access to Hungarian governmental support, but in recent years has tried to absorb UMDSZ and establish a political monopoly in the Hungarian community of Ukraine. This was noticeable during local elections (2020) in Ukraine, when several powerful members of UMDSZ ran as candidates from KMKSZ, which was formally presented as a joint list to the Transcarpathian Regional Council and KMKSZ won eight seats. Zoltán Babják, who is formally a representative of the UMDSZ, ran in 2020 as a self-nominated candidate with the support of both Hungarian political forces, was re-elected mayor of Berehove.

Currently, the Hungarian community does not have a representative in the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhovna Rada), because all three Hungarian majority candidates lost the elections in 2019. The last representative of the Hungarian community in the Verkhovna Rada was László Brenzovics, elected in 2014 on the Petro Poroshenko Bloc list.

There are several funds in Transcarpathia that support the Hungarian community with money from the Hungarian government. The main ones are the Bethlen Gábor Fund, which operates throughout Hungary and abroad, and the Egán Ede Fund, which was launched in Ukraine in 2016. The activities of these funds in Ukraine, or the funds themselves are under control of the KMKSZ and its leadership.

According to the data of the Hungarian Money investigative project, between 2011 and 2020, Transcarpathia received almost 36 billion forints, or about 115 million euros, from the Hungarian government just through the Bethlen Gábor Fund. Of these, Transcarpathian parishes received more than 6.8 billion forints (almost 22 million euros). Another € 62 million was spent on educational institutions, educational programs and travel, books and the reconstruction of schools and kindergartens. Another example: the Egan Ede Fund was established under a special program of financial support for small and medium-sized businesses in Transcarpathia with a budget of 32 billion HUF (at that time almost 104 million euros) for the period 2016-2019. Transcarpathian teachers who teach in Hungarian receive annual subsidies through these foundations.

In 2016, “special envoy” of Hungarian government was established to coordinate Hungarian national policy in Transcarpathia, which has been held for two terms by István Grezsa.

These organizations and foundations also support local media, which mostly work in Hungarian, or cover information about the Hungarian community and Hungary, creating another closed autonomous network. This Hungarian media network in Transcarpathia includes several websites, newspapers, radio and even a TV channel. You can learn more about these media in this report.

National and cultural autonomy is guaranteed to Hungarians by Article 6 of the Law “On National Minorities in Ukraine”. Hungarians also have the right to use their national symbols, and for example, the Hungarian flag can be seen, for instance, at administrative buildings, in particular at the City Hall of Berehove. The political demand for territorial autonomy was on the regional agenda of Transcarpathia during the 1990s; there were even several projects and initiatives to create a separate Hungarian district as an administrative-territorial unit. In a way, this idea was implemented in the form of the Hungarian majority constituency, which existed in the 2002 parliamentary elections. This political demand is still on the agenda as part of the overall vision of national policy of Hungary in Ukraine and Transcarpathia, but without any political grounding or even conceptualization. The idea of Hungarian autonomy was largely shelved following Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine in 2014 through creating pseudo-republics, and made further irrelevant by decentralization reforms in 2014-2020 that shifted much power to municipalities enabling them to in an case operate with greater autonomy. The last time the issue of Hungarian territorial autonomy was raised at the national level was during changes to the administrative-territorial structure of the Transcarpathian region in 2020. At that time 13 districts were consolidated in 6, and Berehove district with the center in Berehove was preserved. In the new version of the Berehove district, the share of Hungarians will be reduced from 76% to 43% (based on the 2001 census).

However, the issue of Hungarian autonomy in Transcarpathia, or its separation from Ukraine and accession to Hungary, is raised in the media in the form of statements by Hungarian right-wing radical politicians and during hybrid special operations, mostly of Russian origin.

As of December 2014, 91.5% of Transcarpathians saw the future of their region as part of a unitary Ukraine. As of December 2018, 81% of Transcarpathians believe that Transcarpathia will be part of a unitary Ukraine, and only 3% – for autonomy within the federation, and 1% – for secession from Ukraine. As of 2020, only 3% of Transcarpathians are in favor of the region’s autonomy within the federal Ukraine, and less than 1% – for the independence of Transcarpathia or its accession to another state.

Ukrainian-Hungarian relations and political tensions: context of last 5 years

Currently bilateral relations between Kyiv and Budapest are at their lowest point since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries in the early 1990s.

Tensions formally started after the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine passed a new education law in September 2017. Article 7 of the law stipulated that “the language of the educational process in educational institutions is the state language”, i.e. Ukrainian. According to the law national minorities, including Hungarians, would retain the right to study in their native language alongside Ukrainian thru the fourth grade after which they would have to gradually switch to Ukrainian. Certain subjects could continue to be taught in English or one of the official EU languages, meaning Hungarian, Romanian, Slovak, Polish and others, but not Russian. A new law adopted in January 2020, concerning general secondary education, clarified that till the fourth grade all subjects, except Ukrainian language subject, can be taught in the native language; in fifth grade Ukrainian language should be used in at least 20% of all “teaching hours” (not subjects) increasing to 40% by the ninth grade and to 60% in the 10th and 11th grades. Focus on “teaching hours” and not of subjects in the law open opened the big possibility for developing bilingual or even multilingual education.

Immediately after 2017 educational law was adopted, the Hungarian community in Ukraine and official Budapest perceived it as an attempt to assimilate, an attack on identity, a breach of Kyiv’s previous commitments to Hungary and internationally, and a narrowing of national minority rights.

Following this, Ukrainian-Hungarian diplomatic tension turned into a deep systemic crisis of bilateral relations over all key issues:

1) dual citizenship and distribution of Hungarian passports to ethnic Hungarians in Ukraine, which Budapest has been actively doing in Transcarpathia since 2011 contrary to Ukrainian legislation which does not recognize dual-citizenship;

2) new Ukrainian education and language laws, regulations of the using Hungarian language in public sphere and call for giving official regional status to it in Transcarpathia, as well as official status for Hungarians as indigenous people;

3) rights for different types of autonomy (cultural, political, territorial, etc.) for the Hungarian community in Ukraine;

4) use of Hungarian symbols in the public sphere, in particular flags on administrative buildings;

5) creation of a “Hungarian district” in Ukraine as an administrative unit for some territorial autonomy, as well as prospects for the restoration of the so-called Hungarian electoral constituency, which operated within Transcarpathia during the 1998 and 2002 parliamentary elections and guaranteed the representation of the Hungarian national minority in Ukrainian Parliament;

6) European and Euro-Atlantic integration of Ukraine (immediately after Kyiv’s adoption of the law on education, Budapest started blocking Ukraine’s EU and NATO ambitions, in particular using its veto on the Ukraine-NATO ministerial-level commission and other minor decisions;

7) Hungarian officials’ interference into the Parliamentary elections in 2019 and local elections in 2020 elections in Ukraine, as well as into Ukraine’s internal affairs;

8) Russian “soft- and gas-power” in Hungary towards Ukraine, as well as Russia’s malign influence and hostile hybrid operations to provoke Ukrainian-Hungarian confrontation over the Hungarian community in Transcarpathia;

9) financial support of the Hungarian minority in Transcarpathia region by the Hungarian government, its transparency and coordination with the Ukrainian authorities. According to Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó, as of 2020, the Hungarian government has invested more than 250 million € (90 billion HUF) in the Transcarpathian region through various programs;

10) operation of Hungarian funds in Transcarpathia and the investigation of their activities by the Ukrainian security service;

Each of these issues is still on the agenda of Ukrainian-Hungarian relations. For the last five years Kyiv and Budapest adopted different approaches but have been unable to resolve any of these key topics.

Moreover, along with debates over this list of Ukrainian-Hungarian issues, Ukraine and Hungary mutually expelled consuls and numerous state officials from both sides were banned for entering the neighboring country. Ukrainian security service initiated an official investigation into the Egán Ede Fund, and personally against its president László Brenzovics, who left Ukraine after the SBU searched his house in Uzhhorod in late November 2020. Since autumn 2020, the state secretary for national policy, Árpád János Potápi, as well as the special envoy of the Hungarian government, István Grezsa, are persona non grata in Ukraine for interference into Ukrainian elections and internal affairs.

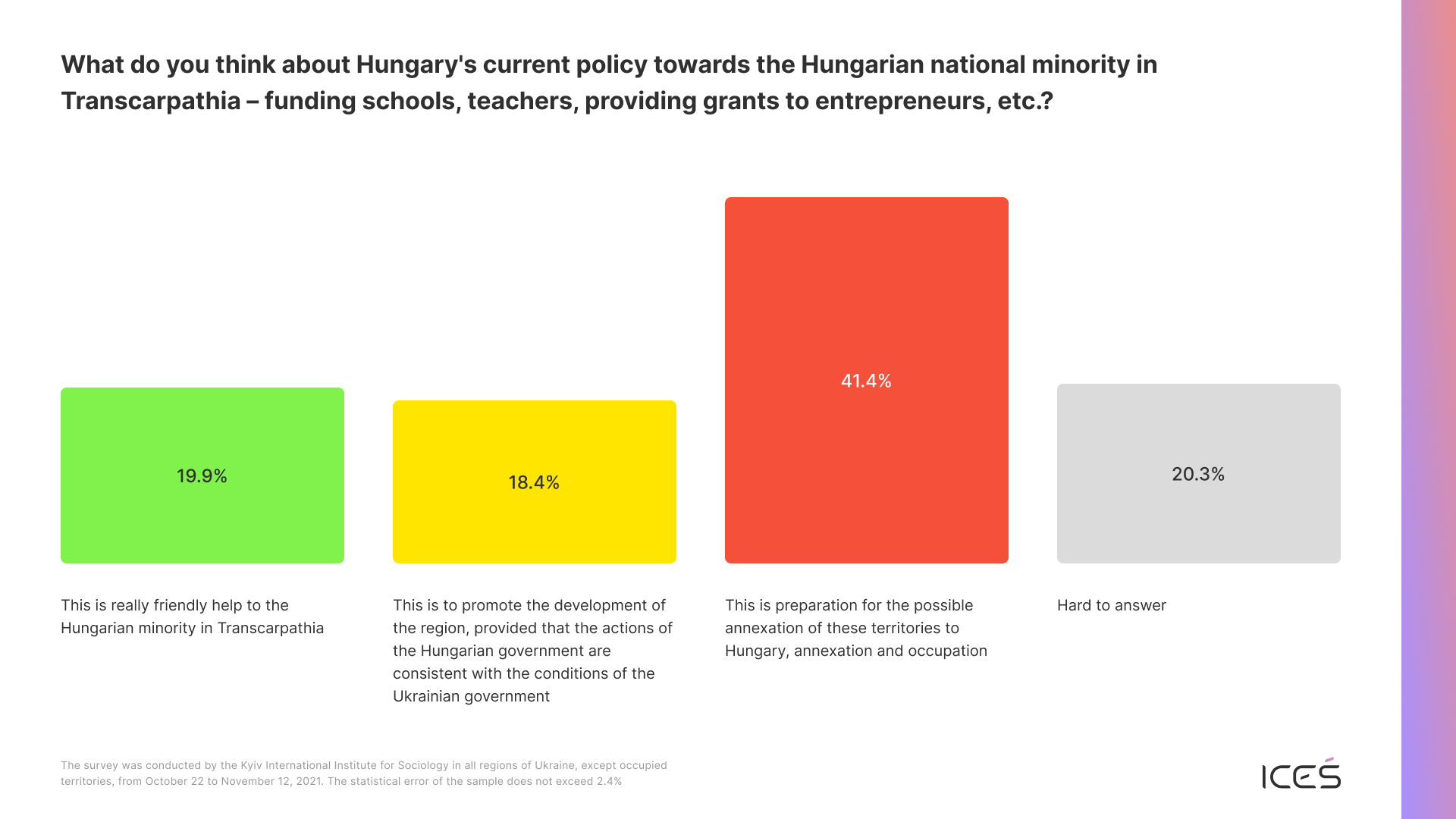

According to a survey commissioned by the Institute for Central European Strategy and conducted by the Democratic Initiative Foundation in all regions of Ukraine, except the occupied territories in late 2021, 41,4% of Ukrainians think that Hungary’s current policy towards the Hungarian minority residing in Zakarpattia – particularly with respect to financing schools, teachers, and grants for entrepreneurs – “aims at preparing a possible annexation and occupation of these territories to Hungary”. Only 19,9% think “this is really a friendly aid for the Hungarian minority of Zakarpattia” and 18,4% believe it “is conducive to the development of the region as long as these activities of the Hungarian government are coordinated with the Ukrainian government”.

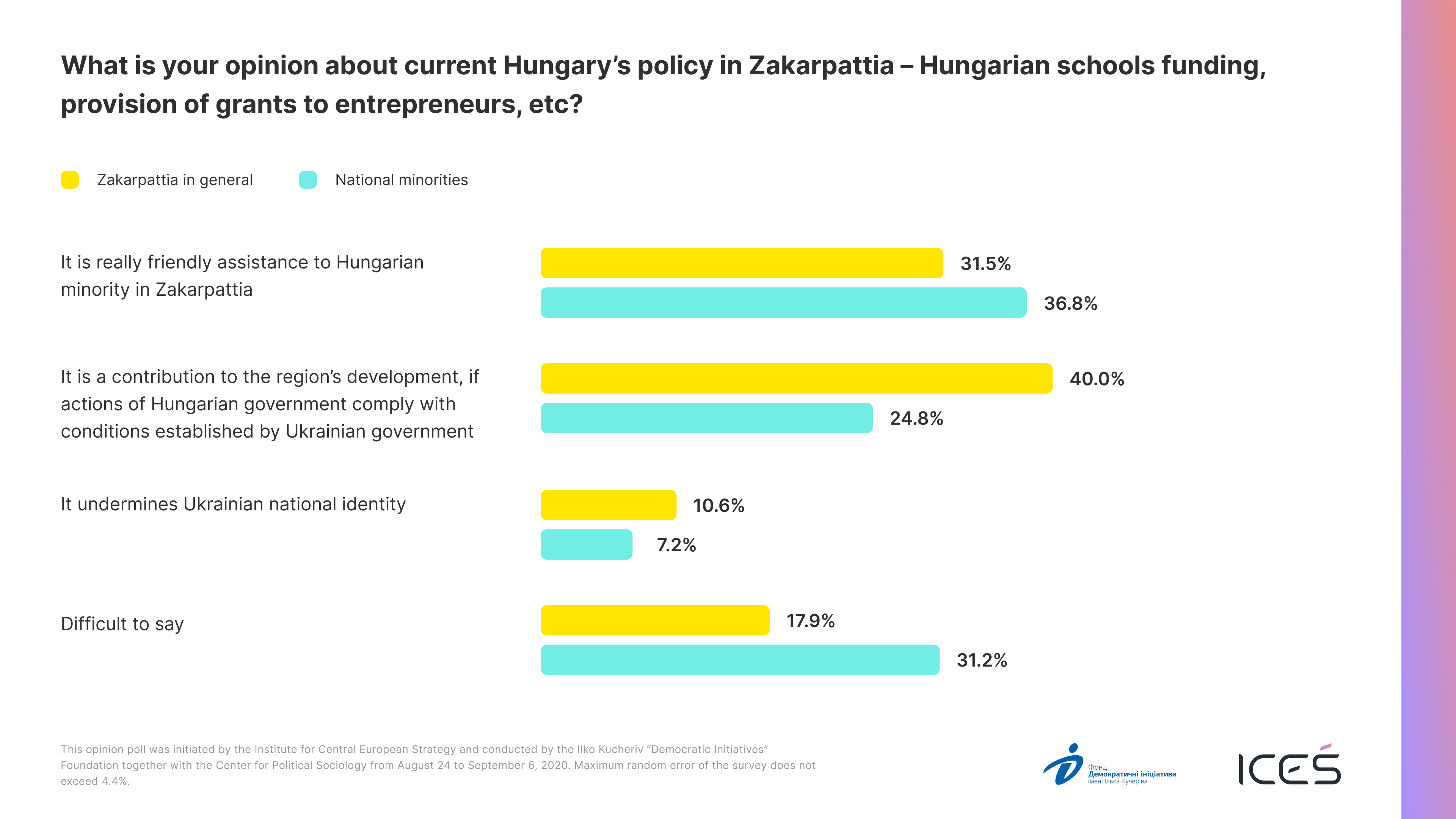

According to another survey, conducted just in Transcarpathia region year before, locals answered almost the same question totally different with 31,5% stating that Hungarian governmental policy towards Zakarpattia is “really friendly support assistance to Hungarian minority”, and 40% answered that this contributes to regional development.

Despite ongoing political and diplomatic debates it is important to emphasize that according to the both polls mentioned above, there is no tension or hostility on the people-to-people level.

In the wake of Russia’s full scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the Hungarian government, on one hand, supported basic sanctions against Russia and received refugees from Ukraine, but other the hand, Viktor Orbán stated that Hungary must “stay out of the war” and the Hungarian government doesn’t plan to supply Ukraine with weapons as well as banning the possibility to transport weapons through Hungary directly to Ukraine. This lays the ground for a new wave of Ukrainian-Hungarian tensions.

Hungarian minority of Ukraine in Hungarian Parliamentary elections 2022

Starting in the 2014 parliamentary elections, Hungarians abroad, who have Hungarian citizenship as a second (dual), can also vote. Such Hungarians have citizenship without registration in Hungary, so they can only vote for party lists. This is 93 seats out of 199. Another 106 members of the Hungarian parliament are elected by majority constituencies, and are voted for by Hungarian citizens with a residence permit in the respective constituency.

Hungarians abroad without registration in Hungary can vote by mail. To do this, they must register for postal voting. The deadline for postal voting on April 3, 2022 is March 9.

This is the legal framework for Hungarians of Ukraine to participate in elections in Hungary. The exact number of such voters in Ukraine is non-public information due to the fact that dual citizenship is officially illegal in Ukraine. In this report, we have already provided data how many ethnic Hungarians live in Ukraine according to official census in 2001 (151,5 thousand), the number of applications for Hungarian citizenship as of 2015 (124 thousand), as well as the results of a survey of Hungarian scientists in 2017, how many Hungarians actually live in Transcarpathia (131 thousand).

However, another figure that gives an approximate understanding of the share of Hungarian voters in Ukraine is the number of voters who voted for Hungarian parties in the last election. In particular, the number of voters who voted for the KMKSZ party as the only Hungarian in the elections to the Transcarpathian Regional Council.

In the local elections of 2015 it was 41,517 votes, in the last local elections in 2020 it was 39,049 votes.

This is exactly the number of Hungarian voters that the ruling Fidesz-KDNP can count on, which since 2010 has increased influence on Hungarians abroad in neighboring countries through governmental programs of support and local political allies, almost in status of the satellites.

Since the Hungarians abroad received the right to vote, only the Jobbik party has tried to intensify its work in Transcarpathia, but without success. Today, there is every reason to say that Fidesz-KDNP has a monopoly on influencing the Hungarian electorate in Ukraine.

Due to the difficult bilateral relations of recent years, as well as the de facto ban on dual citizenship in Ukraine, campaigning of Hungarian politicians in Transcarpathia is not possible. But this fact is compensated by the indirect and covert campaigning of the ruling Fidesz-KDNP team through Hungarian government policy and politics in the Transcarpathian region.

The influence of the mentioned about 40,000 votes of Transcarpathian Hungarians on the final result of the parliamentary elections in Hungary is determined by the turnout mainly. In the last parliamentary elections in 2018, the turnout was 70%, which is 5,791,868 votes. In 2014 – almost 62%, and it was 5,047,363 voters. Extremely simplistic mathematical calculations make it clear that neither with the turnout of 62% or 70%, 40 thousand voters do not give a single seat in parliament.

According to preliminary forecasts, the historically high turnout is expected on April 3, 2022, which further reduces the importance of the votes of Hungarians from Transcarpathia.

However, already several reliable journalistic investigations show that Transcarpathian Hungarians could vote in the 2014 and 2018 parliamentary elections not only for party lists, but also for majoritarian candidates in single-member constituencies on the basis of fictitious residences. This phenomenon is already known as “voter tourism” and it is very relevant for the eastern regions of Hungary bordering Ukraine, in particular the Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg region.

For example, between the 2014 and 2018 parliamentary elections, the official population of village of Kispalád near Ukrainian-Hungarian border changed in few times – from 623 inhabitants in 2014 to 1296 in 2018 and once again to 630 inhabitants in October 2021.

The scheme is such that on election day, Hungarian voters are brought by bus from Ukraine to border settlements where they have a legal residence permit (although they do not live there), and these voters vote for both party lists and majoritarian candidates. And in this case, the weight of the already mentioned above 40 thousand votes from Ukraine is growing.

At the same time, the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began on February 24 2022, created conditions for the election campaign in the context of war, humanitarian catastrophe and migration crisis. According to the UN, as of March 12, Hungary had received 246,206 refugees from Ukraine. It is impossible to count exactly how many, but it is possible that among the refugees from Ukraine there are also ethnic Hungarians with a second Hungarian passport, who if not yet registered in Hungary, may still have time to get it before the election day and be included in the voter lists in constituency levels. This can be done no later than 7 days before election day, as the deadline.

Given all this, despite the relatively small number of potential voters from Ukraine, their participation in the Parliamentary elections in Hungary on April 3, 2022 may affect the results in individual constituencies, as well as undermine the legitimacy and integrity of the elections in general.

* This report as a part of the “Election Monitoring in Hungary and its Diaspora” research is conducted with the support of the International Republican Institute’s Beacon Project. It is conducted in Hungary and select countries with a significant Hungarian diaspora: Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine.

Source: International Republican Institute, The Beacon Project

Featured photo illustration by János Nemes/MTI