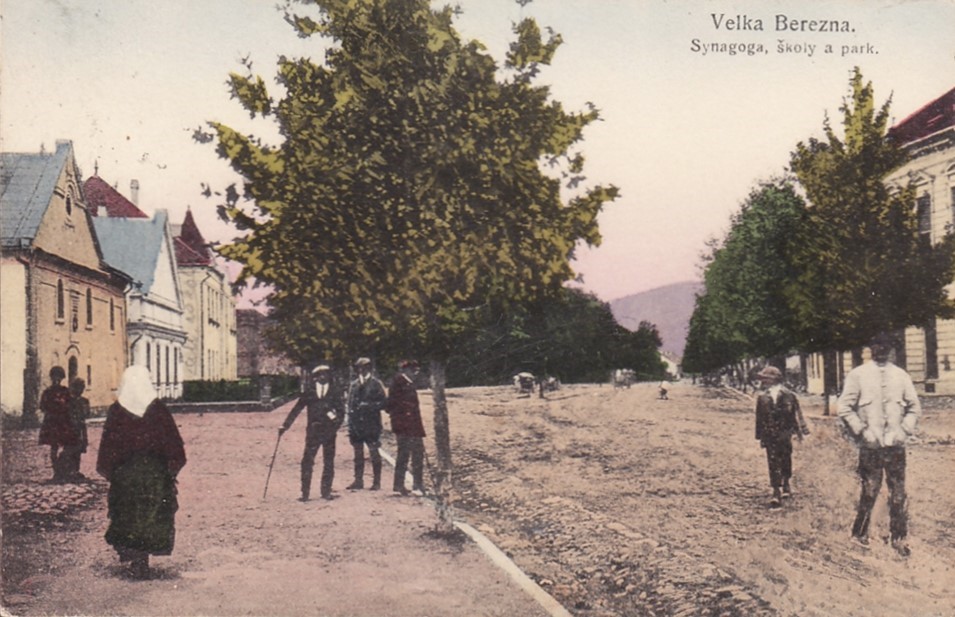

When you come to Velykyi Bereznyi, you find yourself in an absolutely twin-peaks-like atmosphere inherent to most towns located in Zakarpattia. There you will see a few streets, two monuments to Shevchenko the poet and Soviet soldiers, a Holy Trinity Church, arboretum parks of the middle of the 19th century, a local history museum and a Roma camp hosting those representatives of these people who are anarchist and live without a rom baro. The town is encircled by mountains.

Having mountains around you is always good. There are mushrooms and trees are felled there. You could be doing that. What else is an ordinary inhabitant of this region doing? Tourism? Come on, there is no such thing there.

In order to be engaged in tourism, you should offer something that can make people interested. Especially, when we are talking about international tourism.

This region forms a triangle of the border area. Poland and Slovakia are near. Uzhhorod is a stone’s throw away. You can come here to take a stroll in the forest. So much for tourism. However, that’s already a fair number of attractions.

The inhabitants of Zakarpattia do not pay much attention (or they simply know nothing about them) to the famous and significant people who were born in this region due to a long distance to big cultural centers.

The only way to break the vicious circle of this total parochial mentality and some sort of inferiority complex is to shift the focus on these renowned figures, to take a closer look at them, and in so doing to join the world and civilization.

The reluctance to learn and to see things around, especially something that runs counter to one’s notion of the outside world is a typical quality of the local mentality that I have managed to observe on many occasions. However, this topic is a matter of a separate conversation. This quality does not set the inhabitant of Zakarpattia apart from the rest of ordinary Ukrainians. Perhaps this negative quality manifests itself more clearly with people residing in this region – hermeticism and suppression of landmark events as the main character trait.

While searching for some materials for my work, I discovered a few famous figures that can help Zakarpattia join the global world of culture and that can help erect cultural bridges. Those figures are hardly known to anyone here. A few columns on this topic will be published soon.

Here, in Velykyi Bereznyi, Emile Lahner was born, the world-class artist and a representative of classic modernism. He was a renowned representative of the Paris School and one of the founders and communicators of abstractionism.

As is commonly known, at that time Carpathian Ruthenia was part of Austria-Hungary. He was born into a family of immigrants from Alsace (in Zakarpattia there were several large-scale resettlement of Germans – from Saxony, Swabia and Alsace) in 1893, and emigrated to Paris in 1924.

Thus, he spent 31 years in Zakarpattia.

His mother died while giving birth to her child, and when Emile was 7 his father passed away. The 7-year-old orphan was educated and cared for at the court of a local bishop. He was encouraged, as is often the case when the social pyramid ends with a notary at its top, by a priest and a village teacher to study to be an engineer. There was no university in Zakarpattia. Nor was there any high school where one could learn art. Nevertheless, he wanted to be an artist and he eventually became one. He studied to become an engineer in Banská Štiavnica (now in Slovakia), and only after that did he enter the Budapest Academy of Arts, in the studio of the famous professor of the time, János Vaszary, who had ties to a French school. It was there that he studied further. During his studies, Lahner went to Lausanne and went to the exhibition of post-impressionists. Under these powerful impressions his evolution took place.

Subsequently, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was founded and a skirmish with the Red Terror began in this region. Thousands of people were killed or imprisoned. Zakarpattia also underwent all these processes. Times were turbulent and there was no opportunity for Lahner to do things he wanted to do, given that atmosphere of repression. He took a decision to emigrate to Paris, as did hundreds of intellectuals and creative people.

He continued his studies there. He studied in the studio of the legendary artist Antoine Bourdelle, a student of Rodin. This introduced him to the circle of the international Paris school of the interwar period. He lived in the Latin Quarter and Montmartre, that is, in the concentration of progressive people and thoughts of the new time and new art. Back in the days he worked as an artist for cinema and Parisian theaters. In particular, his teachers were the director Alexander Korda. The latter is now considered a British director, but he was also an emigrant from the disintegrating Austria-Hungary, and was even a member of the government of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, where he was involved in the nationalization of cinema. However, after the establishment of the fascist dictatorship, Horthy left Hungary, as did Lahner. This brought them closer.

With time exhibitions of Lahner’s works took place all around the world, in Paris, New-York, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Boston and other cities. He made a name for himself. He travelled a lot in the 1940s.

He studied the paintings of Paleolithic caves in the south of France. These practices led him to combine the plasticity of Altamira’s primitivism with abstractionism, of which he is actually the founder. He was engaged in monumental art. He made stained glass windows and frescoes at a church in French Algeria in the city of El Affroun. His chapel of St. Martin, where he had already used his plastic schematism on the verge of abstraction, caused a great resonance among the French public of the time. In general, he was closely associated with French Africa, having undertaken numerous trips there. He created lots of works afterwards. He was a close friend of the President of Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor, who apart from his political activities, was a well-known poet, a graduate of the Sorbonne, a professor at various French universities, a cultural theorist and the author of the concept of Negritude.

In the 1950s he was a friend and opponent of Pablo Picasso. As a result of the discussions, Picasso offered him a joint exhibition to clarify and emphasize his artistic principles, which took place in 1954. Few people had a joint exhibition with Picasso, especially with Picasso having already become a legend. This is a significant fact. It was a great success in the early 1960s. His exhibitions around the world and everything related to it brought him lots of success. His large exhibition in 1961, at the Castel Gallery in Paris, which took place under the patronage of Senegal’s President, Léopold Sédar Senghor, earned Lahner him worldwide recognition. His exhibitions were successfully held on both sides of the Atlantic.

During the last period of his life, Lahner continued to work at his villa in Vence, Provence, where he kept conducting his plastic experiments. He went through different stages as an artist – post-impressionism, fauvism, cubism, primitive art, abstractionism, synthetic art. All of them fit very well into the system of development of modernism of the twentieth century.

He died in 1980 at the age of eighty-seven as a world-famous artist. Of course, there is no monument to him in Velykyi Berezny. Who cares about the Paris school? And it is clear that we have a superfluous number of such representatives of this school. Who cares about a great world-class artist? I suspect that had Lahner been a famous footballer, the interest in him would have been much greater.

After I published a post on Facebook four years back, having learned about Lahner and described his biography, which, as is often the case in my practice, had completely been reprinted by local publications, his name appeared in the article about Velykyi Bereznyi on Wikipedia. However, this link will lead you nowhere since we don’t even have an article about it on Wikipedia.

It is interesting that this figure has not yet been studied at all. Even in France and in the West in general, only now do they begin to comprehend his artistic heritage. I am trying to say this initiative could be intercepted and elaborated. This artist could become an iconic figure here, his name could be promoted and various cultural initiatives could be launched around it. Culture, as it is done all over the world, attracts business and investment. This is how I would outline in broad-brush terms the prospects for those interested. After all, my job is to bring the topic up.

He deserves a monument. It would perfectly fit in between the Soviet soldiers and Taras Shevchenko, providing a strong contrast to these standard Soviet monuments ubiquitous in all of the former Soviet countries.

Oleksa Mann, exclusively for Varosh

*** This material has been published as an author’s column. Varosh’s editorial team may not share the views and opinions expressed by the author in this publication.